These are my notes for the K5M Book Club on the book Money, by Jacob Goldstein.

A Brief History of the Euro (and Why the Dollar Works Better)

I thought this chapter was going to be boring because for the first few pages I didn’t really highlight anything or take notes, but then it really gets good later in the chapter!

What is a “Technocrat”?

Germany elected a bunch of technocrats and something about that word seems like it has a negative connotation… what’s the deal? What is a technocrat?

“Technocracy is a system of government in which a decision-maker or makers are elected by the population or appointed on the basis of their expertise in a given area of responsibility, particularly with regard to scientific or technical knowledge.”

That seems great. What else?

“This system explicitly contrasts with representative democracy, the notion that elected representatives should be the primary decision-makers in government, though it does not necessarily imply eliminating elected representatives. Decision-makers are selected on the basis of specialized knowledge and performance, rather than political affiliations or parliamentary skills.”

Uh, yeah, that makes sense to me. Am I a technocrat?

“Technocracy privileges the opinions and viewpoints of technical experts, exalting them into a kind of aristocracy, while marginalizing the opinions and viewpoints of the general public.”

Okay, sure… we can’t let industry experts and capitalists make all the decisions. I mean, that could lead to something like…

As major multinational technology corporations (e.g., FAANG) swell market caps and customer counts, critiques of technocratic government in the 21st-century see its manifestation in American politics not as an “authoritarian nightmare of oppression and violence” but rather as an éminence grise: a democratic cabal directed by Mark Zuckerberg and the entire cohort of “Big Tech” executives.

Yeah, I mean, fuck those guys, but what about just regular experts who study a subject, as opposed to college dropouts who got lucky and made a billion by undermining our society? Anyway, I guess I’m not a technocrat.

End of the Deutsche Mark

I didn’t know that a single currency for Europe was part of the bargaining that happened to unify Germany! Did you know that?

I was in Germany in 1997/98 and had no idea that the Euro was in the works. I mean, I was a dumb 20 year old kid in the Army, but still, no idea at all that this major financial shift was being argued and negotiated during that time.

Billions of Euro Notes

The euro came into existence January 1st, 1999. I was living in Portland, OR at the time and I don’t remember this being on my radar. To be fair I was living in one-step-above a punk house trying to make ends meet on dead end jobs and doing internet projects with friends.

Goldstein says “the rollout, which involved printing billions of euro notes and changing over tens of thousands of ATMs, was a logistical triumph.” But interestingly the Wikipedia page says the currency was entirely virtual on its launch in 1999 and the physical notes and coins didn’t start to circulate until 2002.

Banks issued “starter packs” containing small amounts of euros starting in December 2001 to familiarize people with the new money. Finally, a year later, the euro formally entered the world as legal tender. The first official purchase took place on the far-flung French island of Réunion, where euros were used to purchase a pound of lychees. (History.com)

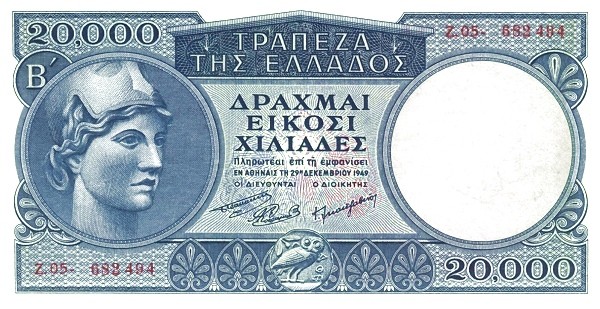

Greece

The foreboding in this sentence is pungent:

European bank regulators started treating bonds of all eurozone governments equally; Greek bonds were exactly as safe as German bonds.

(I do miss all the different kinds of money.)

And then Greece borrowed too much and was fucked. I really like Goldstein bringing back the “morality tale” from issue and highlighting that the borrowing is as much the fault of the borrower (Greece) as the lender (Germany). He calls it two sides of the same coin, and points out the the United States can borrow trillions from China because the United States can just print a new trillion to pay it all back. But when you’re borrowing in someone else’s currency, you are fucked.

Yanis Varoufakis

One of the first economists I ever paid individual attention to was Yanis Varoufakis. Not because of his work as the Greek Finance Minister, or the publication of his many works, but because in 2012 he spent time as the economist-in-residence at the video game company Valve.

Varoufakis says that working with in-game economies are an economist’s “dream-come-true,” as he actually has access to data from every transaction, and doesn’t need to rely on statistics. At Valve, he intends to perform plenty of data mining, experimentation, and calibration of the company’s services to players based on his findings.

Oh, and it looks like they are hiring?

Control

In considering the Euro, Goldstein tells us “why it’s so powerful for a country to have control over its own money.” And I can’t help but think, if that is true, why it wouldn’t also be true for a region, a state, or city, a company, or even a person?

The biggest takeaway of this chapter, and the part that feels IMPORTANT is when Goldstein says:

This is the beauty of borrowing in your own currency: it’s your money, and you can print more if you want to.

Probably because I’m a publicly traded person, but that idea really resonates with me. And with the trends in DeFi and NFTs it seems like something we are all going to have to get used to dealing with.

At the end of the chapter Jacob Goldstein says:

Money is trust; in the modern world, where central banks have the ultimate power over money, money is trust in central bankers.

But the current trend, and the next chapter, is all about decentralized money…